|

Controversial

Elections

Below is a list of some of the

more controversial U. S. Presidential Elections. Scroll down for the

whole list or click on a specific year to read the story. You

can also click here to

find a list of third party candidates that have received Electoral

votes in the past.

1800

1824

1836

1872

1876

1888

2000

1800

(Thomas

Jefferson - John Adams)

In the 1800 Presidential election, the Democratic-Republicans

ran Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr on their ballot. Jefferson and

Burr won a clear majority of the national vote. All 73 Democratic-Republican members

of the Electoral College voted faithfully, casting two

votes each, one for Jefferson and one for Burr. Before the 12th Amendment, Electors

cast two votes for their party without specifying one as being for

the President and the other as being for the Vice President. Because

of this, Jefferson and Burr received exactly the same number of

Electoral votes and the election was a tie. Since there was no majority within

the Electoral College, the decision was deferred to the

House of Representatives, then controlled by the Federalist Party. Though

Jefferson was clearly the Democratic-Republican�s candidate for President, the

Federalist Party considered Burr to be less

of an evil than Jefferson. They tried to rally support

for Burr in place of Jefferson. Burr also refused to endorse

Jefferson. The House had difficulty

coming to a majority and cast 36 separate votes within one

week. Though the original election was in November, the final House

vote, electing Jefferson as President, did not occur until

February 7, 1800. Aaron Burr was appointed as Vice

President. This election prompted the

passing of the 12th Amendment which introduced double balloting. The

Electoral College now casts two separate votes, one for President

and one for Vice President.

Back To Top

1824

(John Q. Adams - Andrew

Jackson)

This was the first election where the winner of the popular

vote did not become the President. Andrew Jackson won a slight

plurality in the popular vote, leading John Quincy Adams by 38,149

votes. Four candidates received Electoral votes, though none

received enough to constitute a majority:

Andrew Jackson received 99 Electoral votes.

John

Quincy Adams received 84 Electoral votes.

William H. Crawford

received 41 Electoral votes.

Henry Clay received 37 Electoral

votes.

Since there was no majority within the Electoral College, the

decision was deferred to the House of Representatives. The House is

only allowed to vote on the top three contenders from the Electoral

College so Henry Clay was removed from the election. Adams, who was Jackson�s most viable

competition, sought Clay�s

support, knowing it would bring him victory. As the vote neared,

Clay worked hard rounding up support for Adams. He won over Western

representatives whose states had voted solidly for Jackson and even

promised the votes of his home state Kentucky, which had not cast a

single popular vote for Adams. After more than a month of

bargaining, John Quincy Adams took precisely the 13 states he needed

to win, Jackson won seven, and Crawford won four. When Adams became President, he

appointed Henry Clay as Secretary of State. Many have suspected that

the promise of the position was why Clay agreed to support Adams.

Jackson called the whole situation a "corrupt bargain" and spent

the next four years campaigning on how the election was stolen from

him. Though Jackson did win the popular vote in 1824, not all

states recorded a popular vote. In six of the 24 existing states,

the Electoral College members were appointed by the State

Legislature. These six states (NY, SC, GA, VT, LA, DE) comprised

nearly 25% of the electorate. The number of voters for each

Electoral vote also varied considerably. There were more voters in

Indiana, which carried 5 Electoral votes, than there were in

Virginia, which carried 24 Electoral votes. More than three times as

many people voted in Ohio than in Virginia, yet Ohio only cast 16

electoral votes. Some states were won with very

high percentages; Jackson carried 98% of Tennessee�s popular vote,

Adams carried 94% of New Hampshire�s vote. Neither candidate

had national appeal and both were absent on the ballot

in at least one state. Despite these variations in representation, Jackson�s

4-year campaign highlighting the unfairness was successful. He

won the Presidency in 1828, presenting himself as a man of the

people, not the government.

Back To Top

1836

(Van Buren - Richard Johnson)

In the 1836 election, the

Democratic-Republican�s Presidential candidate, Martin Van Buren,

won both the popular vote and the electoral vote. His main competition was the Whig

Party. The Whigs hoped to expose the design of the Electoral College

by running several different candidates in different areas, picking

individuals with a great deal of regional appeal.

The Whigs hoped to win a party majority throughout the

country with this method, which would then allow them to choose the

individual they wished to become President. They were unsuccessful and Martin

Van Buren won the election with nearly 60% of the Electoral votes,

though his popular vote lead was just over 50%. His running mate,

Richard M. Johnson, did not fare so well. Upon hearing the

allegation that Johnson had children with an African-American woman,

the 23 Democratic-Republican Electors of Virginia refused to give

him their votes.

Without those 23 votes, Johnson did

not receive a majority vote within the Electoral College. The decision

was deferred to the Senate where Johnson was finally elected by a

majority vote as the new Vice President.

Back To Top

1872

(Greeley - Grant)

Horace Greeley established the Liberal Republicans

(or Democrats) in protest of incumbent Ulysses S. Grant. Greeley ran

against Grant in the 1872 Presidential election. Though few took

Greeley seriously at first, he gained support throughout the

campaign and eventually gathered 40% of the popular vote, only

800,000 less than Grant. Greeley received a total of 2.8 million votes

and would have received 86 Electoral votes had he not died on

November 29, after the general election but before the Electoral

College convened to cast their votes. With no precedent to guide

them, Greeley�s Electors split the 84 votes among four minor

candidates. Grant had already won an absolute majority of the Electoral votes

so the result of the election was not affected. However, history

was slightly skewed because Grant is credited with defeating

Greeley, 286-0.

Back To Top

1876

(Tilden - Hayes)

One of the most controversial

Presidential elections was between Samuel Tilden and Rutherford B.

Hayes. Tilden, a Democrat, won the popular vote by nearly 250,000 votes,

over 3%. On the night of the election, both candidates, as well

as most of the National media, assumed Tilden was the winner. However,

some Republicans were not willing to give up so easily. The

candidate�s Electoral votes were close and the Republicans contested

20 of them, including 4 from Florida, 8 from Louisiana, 7 from South

Carolina, and 1 from Oregon. Out of these 20 Electoral votes,

Tilden only needed 1 to win the election. Hayes needed all 20.

Without any precedent for this many contested Electoral votes, both

parties agreed to set up a 15 person commission to study the

contested votes and to impartially decide whom each vote should go

to. The commission was made up of 5 Senators, 5 members

of Congress, and 5 Supreme Court Justices. It was originally set up

to include 7 Democrats, 7 Republicans, and one independent who

was expected to be unbiased and nonpartisan. At this time, the

Republicans controlled the Senate and the Democrats controlled the

House. Both parties agreed that the findings of the commission would

be upheld unless overruled by both the House and the Senate. When

the independent who was supposed to serve on the commission was

elected as a Senator, he resigned his position on the commission and

was replaced by a Republican. The commission now had 8 Republicans

and 7 Democrats. Over a series of discussions, the

commission voted along party lines and awarded all 20 votes to Samuel Hayes, the Republican

candidate. Each vote was 8-7, with the Republican majority controlling the decision.

Every decision of the commission was contested by the Democratic

House but was upheld by the Republican Senate. The Democrats

threatened to filibuster but eventually agreed to a resolution that

Hayes would withdraw federal troops from the South, ending

reconstruction and the enforcement of equal voting rights for

blacks. This election was clearly corrupted and has found a place

in every debate over the Electoral College since. For a more complete analysis and

timeline of the 1876 election, see the special website designed by

Harper's

Weekly.

Back To Top

1888

(Harrison -

Cleveland)

1888 was

another election where the winner of the popular vote did not become

President. Democratic incumbent Grover Cleveland had won the

popular vote by a margin of 0.8% (90,596 out of 11,383,320 votes).

Despite this slim popular victory, Republican Benjamin Harrison won

the Electoral College majority (233 out of 401 votes). Harrison won the

Electoral College without the popular vote by winning slim majorities

in his winning states and suffering considerable losses in his losing

states. Six Southern states favored Cleveland by more than 65%.

The reason for this split was the issue of tariffs. The South

strongly favored lowering of the tariff. The Republicans approved of high

tariffs and were unpopular in the South. Tariff reform gave

Cleveland immense support in the Southern states, but the South

alone was not enough to win the election. When elected in 1884, Cleveland

was the first Democrat elected since before the Civil War. He came

back to challenge and defeat Harrison in 1892.

Back To Top

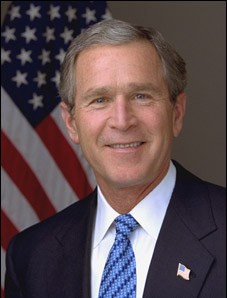

2000

(Bush -

Gore)

The 2000 Presidential Election was the most recent election where

the popular vote winner was not elected. George W. Bush, son of

former President George H.W. Bush, ran on the Republican ticket against

Democratic candidate, and the sitting Vice President, Al Gore. Though

Gore held a slim popular vote victory of 543,895 (0.5%), Bush won

the Electoral College 271-266, with one Gore Elector abstaining.

The election was plagued with

allegations of voter fraud and disenfranchisement. Rumors of illegal road blocks, unclear

ballots, and uncounted votes, particularly in swing states

like Missouri and Florida, were rampant. Florida became the key state as

the election drew to a close. Consisting of nearly 6 million voters,

Florida was officially won by a margin of 537 votes, after a process

of recounting the votes and a Supreme Court ruling. Voters

complained about confusing ballots and many Florida voters believed

that they accidentally voted for Pat Buchanan, a conservative

running on the Reform ticket, when they meant to vote for Al Gore.

Another significant candidate in the 2000

election was Green Party candidate, Ralph Nader. Nader attracted

just under 3% of voters with a progressive platform focused on

social and environmental issues. Democratic supporters targeted

Nader as being a �spoiler� for Al Gore. Since Nader was

left-of-center, Democrats argued that most of his voters would have

otherwise supported Gore. In such a close election, many believe

that Gore would have won if Nader had dropped out of the race. The 2000

election resulted in numerous court battles over contested ballots

and recounts. These lawsuits escalated to the U.S. Supreme Court

where the final, 5-4 decision was made, ending the recounts and giving

the state of Florida's Electoral votes to George W. Bush.

In

the end, Gore conceded the election publicly, though he did

not hide his displeasure at the Supreme Court�s ruling. Back

to Top

CNN's

Election 2000

Archive: complete timeline of the election and links to

several articles

3 Part Article Series:

2000 Election

Electoral College Table

of Contents

|