The GOP Turnout Machine Myth

If it Wasn’t Real in 2004, Why Would it Be Now?

A consistent theme highlighted by pundits during the 2006 election season has been the Republican Party’s alleged advantage in get-out-the-vote operations. A perception reinforced by Republicans’ electoral successes in 2002 and 2004, this alleged advantage fails to hold up to scrutiny of the basis for that recent success. Republicans in fact did relatively poorly in the most hotly contested states in the 2004 presidential elections and did very poorly against Democratic congressional incumbents that year, only defeating one U.S. Senator and one U.S. House Member outside of those running in re-gerrymandered seats in Texas. What drove Republicans’ electoral success in 2004 was not a “72-Voter Project,” “micro-targeting” or an advantage in volunteers focused on get-out-the-vote; rather, they had an edge in basic voter preference. If it had been left solely to which party mobilized more new voters, the Democrats almost certainly would have won the presidency and done better in congressional elections.

Consider the 2004 presidential race. Nationally, George Bush increased his share of the two-party vote from 49.7% in 2000 to 51.2% in 2004, going from a 500,000 vote deficit to 3.5 million vote lead. But this national increase was not due to campaigning in most states. Senior consultant Matthew Dowd said in August 2004 that the Bush campaign had not polled a single person living outside of 17 potential battlegrounds since the campaign got underway in 2002, while during the final five weeks of the campaign, more money was spent by the major party campaigns on advertising in Florida than the combined totals for 45 states and the District of Columbia.

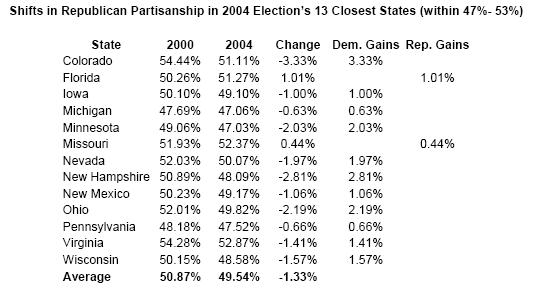

Both parties were most focused on the 13 states that were closest in their two-party partisanship – the ones they knew would tip a 50-50 election. In these battlegrounds, Democrats improved their 2000 performance by a per-state average of 1.33% percent, making gains in 11 of 13 states. While George Bush would have won 10 of these 13 hotly contested states in 2000 had the election been tied in the national popular vote, in 2004 he would have won only five of these states if the election had been even nationally. The fact that Democrats did relatively better in battlegrounds than in the rest of the country suggests that the Democrats’ campaign efforts centered on swing states were in fact more effective than those of the Republicans. It was George Bush’s national advantage in voter preference that carried him to victory, a fact that is underscored by exit polls suggesting that his key win in Ohio was far more based on converting voters who had supported Al Gore in 2000 than winning new voters.

John Kerry’s campaign’s relative success in battlegrounds thus helps explain why there were so few shifts in the Electoral College map despite Bush going from losing by a half million votes nationally to winning the national vote by three and a half million votes. Indeed 47 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia awarded their electoral votes to parties exactly as they had done in 2000. The three states that shifted – New Hampshire (to Democrat), Iowa and New Mexico (to Republican) – were among the five most closely contested elections in 2000. A shift of just 18,774 votes in those states would have meant an exact repeat of the 2000 state-by-state election results.