At-A-Glance: IRV is More Democratic

- Currently, candidates in Oakland have been elected in special elections by

as little as 28 percent of the vote

- IRV allows instant rounds of runoffs which guarantees a candidate receives

a majority

- Currently, voting for a candidate you believe in other than the two

frontrunners is a wasted vote

- By ranking the candidates, IRV makes sure your vote counts

- Currently, Oakland's elections are held in March when voter turnout is

lowest

- Because IRV eliminates the possibility of runoffs, city elections could be

held in November when turnout is highest

IRV and Democracy

There is little more important in a democracy than the citizen's right to vote.

However, in the city of Oakland there are structural flaws in the way our election

system is run that make the process and results much less democratic than they could

be. First, candidates in special elections do not need a majority of the vote to be

elected: in a 2005 special election a candidate won with less than 30 percent of the vote.

Second, our voting system penalizes citizens who vote for long-shot candidates they

most believe in. Third, to accommodate the runoff system Oakland's local elections

take place when many fewer voters show up. Taken altogether, Oakland has a system where

fewer voters elect representatives based upon strategy and not principles in a manner

that could result in the overall least-desired candidate being elected.

Majority Winner

In Oakland, special elections (elections to fill vacancies) are won by a

plurality vote -- whoever has the most votes wins. However, no candidate is

required to receive a majority of the vote to be elected. This means that when

there are four or more candidates, it becomes possible for a candidate to win

with as little as 25.1 percent of the vote! Can an elected official be considered

a representative of the people when a sometimes overwhelming majority voted

against them? In the past five years, two City Council seats have been filled

by special elections where the will of the majority was virtually unknowable:

District 2 Special Election

(May 17, 2005)

| Patricia Kernighan |

28.7 % (winner) |

| David Kakishiba |

21.2% |

|

|

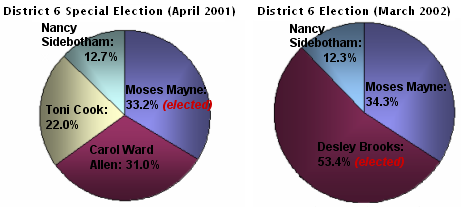

District 6 Special Election

(April 17, 2001)

| Moses Mayne |

33.2% (winner) |

| Carol Ward Allen |

31.1% |

|

The lack of a majority-vote requirement in Oakland special elections is

especially troubling because it is conceivable that a candidate is elected whose

views are diametrically opposed to the will of the majority. For example, in 2001,

Moses Mayne was elected in a special election with 33 percent of the vote. Yet, in 2002,

he lost re-election to Desley Brooks with 35 percent of the vote -- nearly the same

margin he was voted in on! It is possible that a majority of voters disliked Moses Mayne in 2001,

but split their voting power between the other candidates, allowing Mr. Mayne to win by plurality.

IRV solves the plurality-winner problem in special elections because IRV

requires a candidate to receive over 50 percent to be elected. By eliminating the

poorest performing candidate and redistributing his votes according to his voters'

next preference, an instant runoff determines which person voters prefer among the top

candidates. This may occur over several instant rounds until one candidate receives

a majority and is elected, so the will of the people is always known.

Eliminating the Spoiler Effect

The spoiler effect occurs when a voter, by supporting his preferred marginal

candidate, contributes to electing the candidate he least wanted in office. In the

preceding example, Toni Cook might have been the spoiler candidate who diverted enough votes

away from Carol Ward Allen so that Moses Mayne could win.

A more common example would be the 2000 Presidential race in Florida. George

Bush won that state by 537 votes, yet Nader received 97,488 votes. If only 1

percent of Nader voters had voted strategically for Gore, the candidate closest

to their ideological perspective, instead of with their hearts for Nader, then

it is likely that Bush, the candidate furthest from their perspective, would not

have been elected. In that election, quite literally, a vote for Nader was a

vote for Bush. (Note: it could similarly be argued that Ross Perot was the

spoiler candidate for George Bush Sr. in 1992 which permitted Bill Clinton to

win, despite most of the country voting conservative)

There are two evident problems with the spoiler effect: first, it can switch

an election to a candidate who the majority of voters least wanted elected.

Second, it discourages citizens from voting for a candidate who is not considered

to be one of the two top contenders, even if this candidate most represents their

views. Ron Dellums was elected Mayor of Oakland in 2006 with a large majority;

however, a vote for any candidate other than Ron Dellums or Ignacio De La Fuente

was considered by most to have been "wasted".

By allowing voters to rank their choices, IRV eliminates the spoiler effect and

encourages people to vote sincerely. Supporters of Toni Cook could have put her as their

first choice, then selected Moses Mayne or Carol Ward Allen as their second "safety" choice.

In this way, there would be no chance that their vote could be wasted. After San Francisco conducted

its first IRV election, an exit poll conducted by the Public Research Institute found that 46 percent

of San Franciscans felt they were "more likely to vote for their most preferred candidate"

with the new instant runoff system than they had been under the old system, versus only 3 percent

that said it made them "less likely."

Representative Turnout

Oakland elections for local offices are held near June, to coincide with

state and national primary elections. Only in a runoff election, when no candidate

receives a majority of the votes, does a local office election get decided in

November elections, which coincide with state and national general elections.

Unfortunately, because primaries are less popular, this means that most Oakland elections

are decided when voter turnout is at its lowest. For example, in this past Mayoral election,

only 33 percent of eligible Oakland voters cast ballots!

Because primary elections tend to attract more partisan voters, and

fewer minorities, that electorate is less representative of Oakland's

general public than in November. Nonetheless, the local elections

must be held in March in case a runoff occurs, which can then be scheduled for

November.

With IRV, runoffs occur instantaneously (because voters indicate their next

preferences on the ballot) instead of on a separate day, so local elections could

be held in November to maximize voter turnout. The past decade of Oakland elections show that,

had Oakland's elections been held in November, turnout would have been nearly 60 percent higher!

By eliminating the need of a runoff and moving elections to November,

IRV also ensures the candidates will reflect the preference of a wider Oakland

demographic than in the traditional system. (see IRV and Minorities)

Resources

Return to the

Oakland IRV Home.

|

|

|

|