The Democrats' Paradox

Why a Win Could Shake Up House Leaders & The 2008 Presidential Race

Political odds-makers almost universally project a Democratic takeover of the U.S. House this election cycle. Yet few pundits are ruminating over what this might mean for governance, the future of Democratic caucus politics and the 2008 presidential contest. The nature of the districts where Democrats are likely to make gains, as well as the current composition of their caucus, indicate that the party may have to walk a tightrope in both governance style and presidential candidate selection in order to preserve its majority.

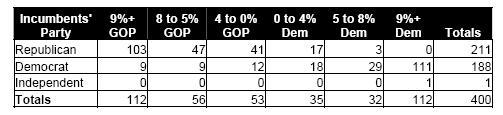

Democrats in Enemy Territory. Heading into the November 7 elections, the Democrats hold 18 seats in districts that have a Republican partisanship of at least 55% - that is, districts George W. Bush won by more than 5% above his national average in 2004. As a point of contrast, Republicans only hold three seats in districts that have a Democratic partisanship of at least 55% (ones John Kerry carried by more than 5% points above his national average). It is for precisely this reason that Republicans may have felt emboldened to pursue a relatively ideological agenda without fear of putting many of their members at risk. Thanks to the geographic dispersion of Republicans across congressional districts, Republicans of the conservative stripe are more numerous and safe than moderates of the Chris Shays variety. Indeed, moderate Republicans are generally the most vulnerable this cycle, but their small number has allowed the party to speak to its base without much fear of Democratic reactions (see table below). A Democratic majority will not have the same luxury.

Potential Democratic Gains in Republican Districts. Meanwhile, Democrats need 15 additional seats to capture a majority. Pundits see roughly 37 seats in play as potential pick-ups – but only 11 of these seats are in districts with Democratic partisanships of 50% or greater. Yet fully 14 of the 37 potential pick-ups are in districts with Republican partisanships of 55% or greater. Even if the Democrats sweep all 11 Republicans out of office in the Democratic districts, they will still need to pick up four more seats in Republican territory in this best-case scenario. Realistically, a new Democratic majority will be composed of more than just 4 pick-ups in Republican-leaning districts. So, combining the 18 Democratic incumbents currently representing strongly Republican districts with at least four pick-ups in such districts, the new majority will rest on more than 20 incumbents in hostile territory, unlike the current Republican majority.

Click the following link to see the chart listing where Democrats may win seats in 2006 and the district partisanship.

Future U.S. Senate Control in Limbo. By most measures, should Democrats win control of the U.S. Senate this November, their majority will consist of a mere 51 seats. Notably, there are 33 Senate seats up in 2008, including six Democratic seats in states that Bush carried in 2004: Mark Pryor (AR), Tom Harkin (IA), Mary Landrieu (LA), Max Baucus (MT), Tim Johnson (SD), and Jay Rockefeller (WV). Of these six seats, four were won by 54% or less in 2002, and Rockefeller is rumored to be considering retirement, which would create an open seat in newly Republican territory. Meanwhile, Republicans will field only four incumbents in states that Kerry won in 2004, and only two of those seats were won with less than 54% of the vote: John Sununu (NH) and Norm Coleman (MN).

Analysis. Post-November 7th the Democratic Party may have to walk a tightrope in order to hold a majority in either chamber of Congress, given that the national political geography provides the Republicans a built-in advantage. The Democratic base will be anxious for rolling back the Republican agenda and aggressively attacking the Bush administration, but Democrats in Republican-leaning districts may be rightly wary of aggressively pursuing those strategies. As a result, leadership elections and caucus politics will be a challenge for the new Democratic leadership, and party elders may seek to provide momentum to a 2008 nominee who will not create perceived down-ticket problems for the potential Democratic majority (as occurred in the 2004 Democratic primary when party leaders were accused of trying to sabotage Howard Dean’s bid in favor of John Kerry). It is yet unclear who will benefit from such a sentiment, but John Kerry notably did not contribute to the down-ticket loss of hardly any congressional Democrats in 2004, including those running in largely Republican districts.