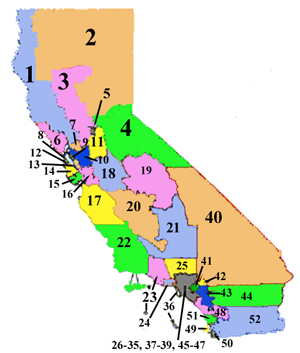

| California’s Political Lineup

| ||||||||||||||||||

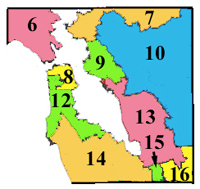

Bay Area

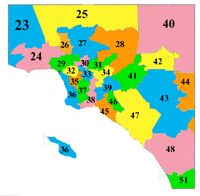

| Los Angeles

|

Redistricting Deadline There are no constitutional deadlines for either congressional or legislative redistricting, but if a deadlock occurs, the impasse goes to the state supreme court. | Who’s in Charge of Redistricting? The legislature. Each house in the California legislature separately draws its own districts. The Elections and Reapportionment Committee draws the state senate plan. The Committee on Election, Reapportionment and Constitutional Amendments Committee draws the assembly plan. The congressional plan is a result of collaboration between both houses. The governor has veto power over both legislative and congressional plans. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Districting Principles

| Public Access The redistricting process is very open in California. The legislature makes a sophisticated database containing ten years of election data overlayed on top of census data. This databaseis maintained by the University of California at Berkeley and is available on the Internet well before public hearings begin. In addition, the database is distributed to major state libraries for public use. The legislature does not supply the districting software, but it is readily available for purchase. The State Senate webpage has a section on redistricting which includes information about: scheduled hearings, submitting plans, and information about the committee. California Congressional Delegation Proposed Districts Maps now online. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Political Landscape In 1982, California provided a preview of modern political gerrymandering, as the late Congressman Phil Burton crafted very Democratic-leaning plans for the state legislature and for Congressional seats. Democrats continued to win comfortable majorities of seats in the 1980s despite Republicans at times outpolling them in the popular vote. Fearing another Democratic gerrymander in 1990, Republicans persuaded U.S. Senator Pete Wilson to run for governor in 1990. Wilson stymied Democrats in the legislature, and ultimately crafted a relatively even-handed plan that was approved by the state supreme court. In 2001, California’s Democrats control both chambers of the state legislature and the Governor’s seat. Democrats will likely attempt to boost their partisan advantage by targeting certain Republican incumbents, creating safer seats for incumbent Democrats and ensuring the state’s one additional House seat goes to Democrats. There also may be a push for more Latino-majority districts, potentially causing some friction with African American incumbents. | Legal Issues In 1990, a successful vote dilution claim was brought in U.S. district court against the Board of Supervisors of the county of Los Angeles. Districts split Hispanic voters in the county among several voting districts. The Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld the trial court's ruling that this violated the Voting Rights Act and Equal Protection Clause of the fourteenth amendment to the Constitution. In the 1990s, however, most local voting rights challenges in California have failed. In a series of cases, congressional, state and local redistricting plans were drawn by a special master appointed by the California State Supreme Court. The plans were precleared by the Department of Justice and adopted by the court in 1992. In 1994, the Mexican-American Legal Defense Fund unsucessfully challenged the court adopted plan on Equal Protection and fifteenth amendment grounds. A later lawsuit against “racial gerrymandering” in congressional districts also failed. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legislation/Reform Efforts Given the state’s contentious history of battles over redistricting, both good government groups and the Republican Party have backed several redistricting reform initiatives in the last two decades. In 1999, Republican activist Ron Unz planned a reform package seeking both campaign finance reform and a redistricting commission, but removed the redistricting proposal after leading Republicans backed an alternative initiative. That proposal would have put the state Supreme Court in control of redistricting, but after backers collected enough signatures to place it on the March 2000 ballot, it was removed by the state Supreme Court as violating the state constitution’s single-subject law (it also would have raised lobbyist fees). Other initiative efforts to reform redistricting were also pursued, but did not collect enough signatures to win a place on the ballot. |

|

Contact Information Sandi Polka Office of the President ProTem of the Senate State Capitol, Room 412 Sacramento, CA 95814 916-327-9178 Fax 916-445-8356 [email protected] Darren Chesin Senate Elections and Reapportionment Committee State Capitol, Room 5046 Sacramento, CA 95814 916-445-2601 |